Organizing your company’s brand architecture can significantly impact marketing strategy, budgets, and growth.

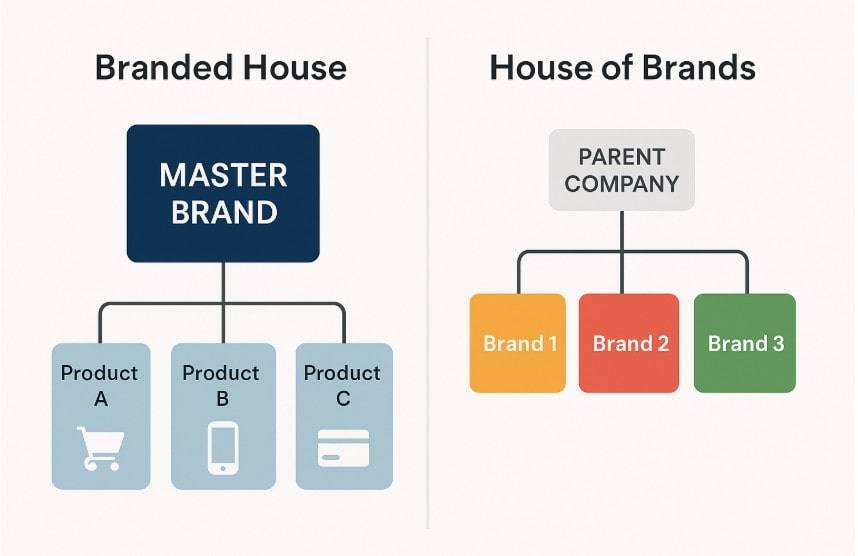

The two ends of the spectrum are branded house and house of brands. In this post, we’ll introduce each concept with examples, then provide a comparison grid of positives and negatives from a marketer’s viewpoint.

Finally, we’ll look at one successful and one less successful real-world change in brand architecture with insights on why those transitions fared as they did.

What Is a Branded House? (One Unified Brand)

In a branded house strategy, the company itself is the master brand. All products, services, or sub-divisions share the primary brand name or identity. The goal is a unified brand experience. When customers trust the main brand, that goodwill extends to everything under its umbrella. A win for one product becomes a win for all.

Example: Apple is a classic branded house. Apple’s products and services – Apple iPhone, Apple Watch, Apple Music, Apple Pay, etc. – all carry the Apple name and ethos. Because of this, Apple can leverage its strong brand equity across every new offering. Another example is FedEx, which offers FedEx Express, FedEx Ground, FedEx Freight, and more – different services, but all clearly FedEx. This consistency in branding builds a cohesive identity and trust: if a customer trusts FedEx for shipping, they’re likely to trust FedEx Office or FedEx Freight, too.

The branded house approach works best when a company’s offerings target the same (or closely related) audience and share common values. All marketing efforts reinforce one name, creating synergy. However, as we’ll see, this focus comes with some trade-offs in flexibility and risk.

What Is a House of Brands? (Multiple Distinct Brands)

In a house of brands strategy, the company operates a portfolio of individual brands, each with its own identity, audience, and marketing. The parent company’s name may be downplayed or even unknown to consumers. This approach intentionally keeps brands separate so each can shine on its own.

Example: Procter & Gamble (P&G) is a quintessential house of brands. P&G owns Tide, Pampers, Gillette, Olay, Crest, Febreze, and many more, but consumers recognize each product brand independently; the P&G corporate brand stays in the background. Another example, Unilever, owns Dove, Axe, Ben & Jerry’s, Hellmann’s, etc., each with unique positioning. Customers may not even realize these disparate products share the same owner – and that’s by design.

This model is all about flexibility. Each brand can have a distinct image and target a specific segment without being constrained by a single umbrella identity. It’s great for tailoring offerings to different markets or price points and for isolating risk (one brand’s crisis won’t automatically harm the others). But maintaining many brands comes with higher complexity and costs, as we’ll explore next.

Comparing the Two Approaches: Pros and Cons

The table below summarizes key positives and negatives of branded house vs house of brands from a marketer’s perspective. This comparison grid is meant to be concise and scannable, highlighting how each strategy stacks up on important factors:

| Aspect | Branded House | House of Brands |

|---|---|---|

| Brand Equity & Trust | Unified brand equity: One brand builds trust that benefits all offerings. Success in one product can boost credibility in others. Customers have a clear, consistent image of the company. | Independent brand equity: Each brand must build trust on its own merits. No automatic carry-over of reputation – but also one brand’s issues won’t tarnish the others. |

| Marketing Efficiency | Cost-effective marketing: Resources are focused on promoting a single brand, which is economical and efficient. One marketing campaign can lift all products. Shared messaging means less duplication of effort. | Higher marketing costs: Every brand requires its own marketing budget, strategy, and campaigns. It takes more time and money to build each brand from scratch. Efforts aren’t shared, so you may need multiple teams or agencies. |

| Brand Focus & Clarity | Clear brand story: Easy to present a unified message and identity. All products align with the master brand’s values and voice, which reinforces a clear market positioning. | Targeted positioning: Each brand can develop its own story and vibe tailored to a specific audience or niche. This allows precise positioning (e.g., one brand high-end, another budget) without confusing customers. |

| Flexibility & Innovation | Constrained flexibility: New products or markets must fit under the main brand’s umbrella. It can be challenging to launch offerings that diverge from the core brand image. Radical innovations might seem off-brand if they stray too far. | Maximum flexibility: Brands have freedom to innovate and even compete with each other. You can enter very different markets by creating or acquiring a new brand for each. If one brand needs a totally different personality or niche, that’s viable in this model. |

| Risk Management | Shared risk: The entire brand shares one reputation – a crisis or failure in one area can damage the whole company’s image. There’s a single point of failure in terms of brand trust. | Isolated risk: Brands act as firewalls for each other. If one product line has a scandal or flops, the damage is largely contained to that brand. The parent company and other sub-brands are less affected by one brand’s troubles. |

| Organizational Complexity | Simplified management: With one brand to manage, internal teams can stay aligned on branding, messaging, and strategy. Brand governance is easier – one logo, one website, one set of guidelines. | Complex structure: Juggling multiple brands means more complicated organization. Each brand may need separate teams or at least dedicated brand managers. Ensuring consistency within each brand (and avoiding internal brand conflicts) requires effort. |

| Market Segmentation | Broad reach, single brand: You use one brand to address multiple segments, which can work if segments are similar. However, if customer groups have very different needs or images of your brand, it’s harder to appeal to all equally under one name. | Niche targeting: Easier to segment markets by assigning different brands to different audiences or product categories. Each brand speaks directly to its target consumers (e.g., one brand for luxury buyers, another for bargain seekers) without one size fits all. |

| Digital Marketing & Data | Unified digital presence: Often a single website and social media presence for the master brand. This simplifies SEO and content strategy (all traffic and backlinks bolster one domain). Analytics are consolidated, giving a holistic view of performance. However, you’ll need to tag and segment data internally to see how individual products perform. Reporting is simpler at the top level (one brand’s metrics), but you must slice data by product/service to get granular insights. | Multiple digital funnels: Likely separate websites, social accounts, and analytics for each brand. This allows specialized SEO and campaigns (each site targets its own keywords and audience). You can dive deep into each brand’s metrics easily. However, reporting across the whole company is more complex – data is siloed by brand. Comparing performance or sharing customer data across brands may require extra integration. Expect to “slice and dice” data across several platforms when presenting company-wide marketing results. |

| Growth & Expansion | Brand stretching: Growth often comes by extending the main brand into new offerings. This can be efficient if the brand’s reputation aids the new venture (e.g., launching Google Drive benefited from the Google name). But if you expand into areas far from your core, the brand may not stretch comfortably or could lose focus. Acquisitions typically get rebranded into the one umbrella, which can risk losing the acquired brand’s loyal customers during transition. | Acquisition ready: A house of brands can readily absorb acquisitions and let them continue under their own names if desired. The company can operate in very diverse fields without confusing consumers (since each brand is distinct). You have the option to keep or change an acquired brand name based on its equity. On the flip side, building a cohesive culture and cross-selling across brands might be harder since each brand is distinct. |

In short: A branded house offers efficiency, consistency, and a strong unified presence, but it puts all your eggs in one brand basket. A house of brands offers flexibility, targeted branding, and risk insulation, but demands more resources and careful management of many moving parts. Many companies actually blend these approaches. For example, a hybrid model where a strong parent brand exists alongside select sub-brands or endorsements (think Alphabet as a parent of Google, or Marriott with both Marriott-branded hotels and standalone names like Ritz-Carlton).

Lessons from Changing Brand Architecture

Choosing between a branded house and a house of brands isn’t a permanent, one-time decision. Companies often evolve their brand architecture as their business grows or strategy shifts. Let’s look at two historical examples: one where changing the brand structure proved effective, and one that faced challenges. These cases provide insight into what can go right or wrong when re-organizing your brands.

Effective Example: Google Becomes Alphabet (Expanding from One Brand to Many)

Google started as a classic branded house – everything from Search to Gmail to Maps carried the Google name. As the company ventured into new arenas (self-driving cars, health tech, venture capital, etc.), leadership saw the need for a structure that could foster these diverse projects without diluting the core Google brand. In 2015, Google surprised the business world by creating a new holding company, Alphabet, and making Google a subsidiary under that umbrella.

This move essentially shifted Google’s organization toward a hybrid brand architecture. Core consumer products stayed branded as Google (maintaining the familiar brand trust), while riskier or non-core ventures (like Waymo for autonomous cars, Verily for life sciences, Wing for drone delivery) were given their own independent brands under Alphabet. The result? Greater strategic flexibility. Each new business can develop its own identity and culture, pursue its industry, and even fail, without casting a shadow on “Google” itself.

From a marketing perspective, this separation helps because Google’s brand can remain focused on tech products and services consumers know, while the more experimental projects can craft specialized brands aimed at their unique stakeholders. It also simplified reporting and accountability: each Alphabet subsidiary could be evaluated on its own, and the company avoided the confusion of vastly different initiatives all marketed as “Google.” By most accounts, this reorganization has been effective – Google’s core brand remains strong, and Alphabet has the freedom to invest in multiple fields. The key insight is that if your one-brand strategy starts to strain under divergent business lines, moving toward a house-of-brands or hybrid model can protect your flagship brand while enabling innovation.

Cautionary Tale: Facebook Rebrands as Meta (Challenges in Re-Architecting a Brand)

In late 2021, Facebook, Inc. changed its name to Meta Platforms, signaling a shift from a single-brand focus to a broader architecture. The company now positions Meta as the parent brand overseeing Facebook (the social network), Instagram, WhatsApp, Oculus, and other products. The rationale was to align with the company’s growing ambitions in the “metaverse” and to differentiate the corporate identity from the Facebook app, which had been mired in controversy. In theory, this is a move towards an endorsed house-of-brands or hybrid structure – “Meta” is an umbrella, and the social apps remain individually branded. Executed well, this strategy can allow each product to stand on its own and prevent issues with one app from directly infecting the reputation of others.

However, Facebook’s rebranding to Meta illustrates that changing brand architecture alone isn’t a silver bullet. Thus far, the shift has had mixed results. On the positive side, Meta as a corporate brand gives the company room to pursue new initiatives (like VR/AR technologies under the Meta name) without everything being tied to the Facebook identity. And indeed, the average user now sees “from Meta” on Instagram and WhatsApp logins, subtly indicating a family of brands. From a marketing data standpoint, Meta can develop separate messaging and communities (the Horizon Worlds metaverse product, for example, has its own branding).

On the other hand, critics note that renaming the company didn’t instantly fix underlying issues. Facebook the app still faces trust and privacy challenges, which inevitably affect public perception of Meta as a whole. In essence, renaming without addressing core problems is only a cosmetic change. As one branding expert observed, renaming can “invite a breath of fresh air” if your business has evolved, but if it’s done mainly to escape a troubled reputation, it may be “too little, too late.” So far Meta’s stock performance and user sentiment suggest that while the new structure could be beneficial long-term, it hasn’t drastically altered the narrative. For marketers, this serves as a caution: shifting to a house-of-brands model for greater flexibility or PR reasons must be coupled with genuine improvements in products and customer experience. Simply slicing data or campaigns by brand (Facebook vs. Instagram vs. WhatsApp) doesn’t remove the need to maintain trust in each. In Meta’s case, time will tell if the new architecture truly enables the company’s next chapter or if consumers simply see it as the same old Facebook under a new name.

Conclusion: Making the Right Choice for Your Marketing Strategy

Deciding between a branded house and a house of brands comes down to your company’s goals, audience diversity, resources, and risk tolerance. From a marketing perspective, it’s crucial to consider how the choice will affect everything from brand storytelling to budget allocation and data analytics. A branded house simplifies your outward message and can concentrate your SEO, content, and advertising efforts for maximum impact on one brand. A house of brands lets you craft pinpoint marketing for each offering and buffer your other brands from any one product’s issues – but requires juggling multiple marketing plans and careful coordination.

Actionable insight: Before committing, envision your marketing and reporting under each model. How will your digital marketing be organized – one website or many? One set of social channels or separate profiles for each brand? How easily can you slice and dice your data to see which product is performing or which audience is responding? As Hinge Marketing notes, measuring ROI for one unified brand is far simpler than doing so across “multiple parallel brands.” Make sure your analytics infrastructure (tracking, dashboards, KPIs) can handle whichever structure you choose. For instance, if you run distinct brands, plan on a way to aggregate results to see the whole company picture when needed.

In summary, both approaches have merits. A startup or professional services firm might lean toward a branded house to build awareness quickly and economically, whereas a conglomerate or consumer products company might adopt a house of brands to capture different markets and minimize cross-brand fallout. Some of the world’s best marketers navigate a hybrid path, selectively applying a unified brand where it strengthens the story and spinning up new brands where customization wins. By understanding the pros and cons through a marketing lens, you can architect your brand portfolio in a way that aligns with your business strategy and sets you up for long-term success.

References and Further Reading

Hinge Marketing – “Best Brand Strategy: Branded House or House of Brands?”

Backstory Branding – “House of Brands vs Branded House: Which One Wins?”

Focus Lab – “From Facebook to Meta: The Power of a Rename”

Brainzooming – “FedEx Office and an Ingredient Branding Strategy”